In late fall, horse racing publications are dominated by articles announcing that many of the male and female equine stars of the racing world have been retired. If the horse is an intact male, he will be retired to begin stud duties. If the horse is a filly or mare, she will trade racing for motherhood and become a broodmare (a female horse used for breeding). This sounds simple enough, but the transition from athlete to parent often involves significant planning and considerable amounts of money.

For a filly or mare, her retirement destination is not always obvious. If a racehorse owner also breeds horses on his or her own farm, it is likely that his or her fillies/mares will retire to his or her farm, which is where the mare will live for the duration of her pregnancies and while nursing her foals. It is also possible for horse owners to breed horses without owning their own farms. In this case, they will pay to board their mares at another farm. For example, commercial farms such as Claiborne, Lane’s End, and Hill ’n Dale keep their own horses on their farms in addition to boarding horses owned by clients.

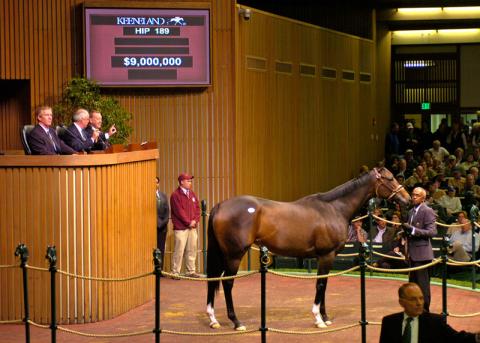

However, not all people who race horses, breed horses, and not all people who race and breed horses retain all of their horses for breeding purposes. In this case, broodmare prospects are sold privately or at public auctions. Two of the most famous sales for broodmare prospects are the Keeneland November Breeding Stock Sale and the Fasig-Tipton-Tipton November Sale. Two-time champion Ashado was consigned to the Keeneland Sale, where she sold for $9 million, while Havre De Grace, the 2011 Horse of the Year, sold for $10 million in the Fasig-Tipton November Sale. A filly or mare’s retirement plans are determined by her sole owner or if owned by one of the horse racing partnerships, the managing partner.

When it comes to successful colts, securing a stud deal is almost always more lucrative than the horse’s total racetrack earnings. A colt may have his retirement plans determined as early as his two-year-old-year or as late as at the conclusion of his racing career. Even though many racehorse owners do own farms, most farms are not home to breeding stallions. Thus, the majority of the top stallions in the United States are kept at farms who specialize in standing stallions at stud.

For the top farms, a colt usually needs to win at least one Grade I race (Grade Is are the most prestigious races) to become a sought-after stallion prospect. Once a colt wins a Grade I, his owner’s phone will start ringing with offers from stud farms. Stud farms aim to purchase the breeding rights of top colts and often divide the ownership into a syndicate (think horse racing partnerships) of shares upon retirement. Although the stallion will live at one farm, he may end up with dozens of new owners who own one or more breeding shares. These shares entitle the owner to a range of benefits including a share of revenue from the horse’s stud fees and free breedings to the horse with the shareholder’s own broodmares.

The colt’s owner may choose to sell all of the horse when he retires, but most retain some shares so that they can continue to profit from the horse after he leaves the racetrack. Secretariat made headlines in 1973 when he was syndicated for a record $6.08 million…BEFORE he won the Triple Crown. Fusaichi Pegasus, winner of the 2000 Kentucky Derby, was syndicated for about $50 million!

Regardless of a top horse’s gender, its breeding future is carefully planned so that it is afforded the best opportunity for success and its owners on the racetrack or in retirement can optimize their chances for profitability.